Written by Dimitris Tzouris, Infrastructure Developer for Humanities Commons

In November, we celebrated one year from the launch of hcommons.social, our Mastodon instance. As of today, more than two thousand members have registered, with new ones joining daily.

Mastodon is a free, non-profit and open source social network and microblogging service that can be self-hosted. It is part of the fediverse, a collection of federated services that communicate and interact with each other using the ActivityPub protocol.

The impetus that set hcommons.social in motion was the rapid downturn Twitter had taken after the changing of its ownership in late 2022, which resulted in many users leaving the service. It was a turbulent time for social media, with connections breaking and people losing networks that had taken many years to build and foster. Therefore, hcommons.social had to be born in order to provide a safe alternative, not just for academics and scholars, but also for anyone with an active interest in research and education looking for refuge – a place to begin again. As people were flocking to various other social networks, hcommons.social started as a trusted shelter for anybody looking to reconnect with their online peers in a safe space and down the road, it has become so much more. What follows is a look behind the curtains at how hcommons.social came to be and what goes into running and maintaining it.

Not the smoothest rollout

For us, rolling out the new service came with some bumps. We started out using a pre-built version of Mastodon, provided as a one-click install by a cloud computing service called DigitalOcean. Unfortunately, the specific version of Mastodon was old and we ran into all kinds of problems when we tried to update it. It turned out that everything the service was running on was old, so we had to do a complete rebuild from the ground up. Migrating from the original version database to a newer one was extremely challenging, but thanks to Steve Ramsey’s support, we got it stabilized. At that point, we had chosen to switch to a Mastodon fork called Hometown and its author, Darius Kazemi, provided some key help. What made Hometown stand out for us is that it provides the ability to restrict publication of a post to just the hcommons.social community. This means that followers registered on other Mastodon instances are not able to see a post and hcommons.social users are not able to repost it on other instances. This provides an additional layer of safety and protection for our users.

The lag

As new members started joining daily and the total number of registered and active members kept increasing, people using Mastodon started experiencing slowdowns. With the situation at Twitter becoming more dire week after week, this became a regular challenge for the influx of new users. The reason for the lag was the way a service called Sidekiq is set up by default. Sidekiq is an open source service that handles scheduled tasks that run in the background. Mastodon uses it to send emails, push updates to other instances, forward replies, refresh trending hashtags etc. All these tasks are placed in different queues and they are handled by separate processes, based on the type of task. Each process has a number of threads, which makes it possible to run tasks in parallel.

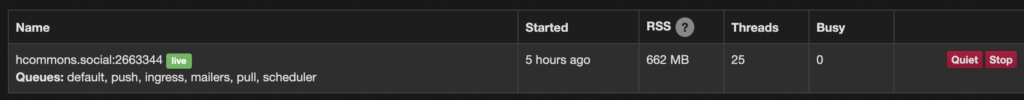

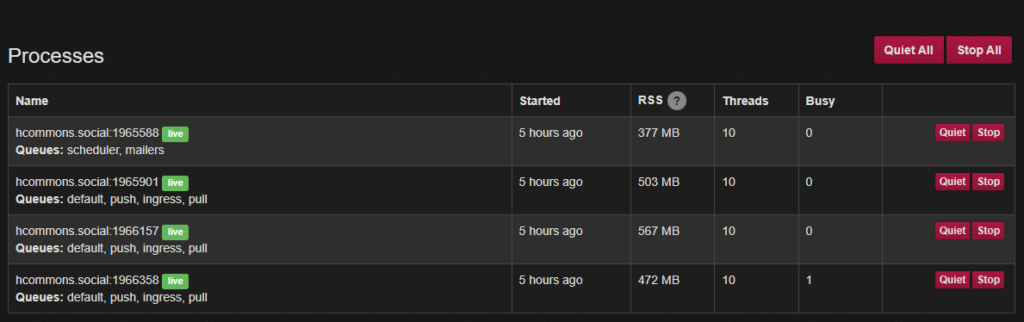

By default, Sidekiq was set up with only one process handling all queues using 25 threads. This meant that all background tasks were handled by the same process, thus creating a bottleneck.

This caused lag when there was increased activity, sometimes resulting in posts getting pushed hours later. Users’ feeds were slow to update and the posts were from much earlier.

To deal with that, we had to reconfigure Sidekiq. The new setup would include the scheduler and mailer queues in their own process and three other processes which would deal with all other queues in parallel. Each process now has 10 threads, which are more than enough with our existing database infrastructure.

Which brings us to another major issue.

The database

At first, a 30-GB managed database on DigitalOcean sounded like more than enough storage, along with additional object storage for files. Well, 12 months and 2050 users later, the database storage we were using had ballooned to 42 GB. The reason for this rapid size increase is the way the fediverse works. When people follow accounts from other Mastodon servers, the local instance caches the posts, along with all the attached media. To deal with the increased storage demands, we did two things:

- Each day, we started cleaning up about 15 GB of old cached media on the server, using a shell script that runs with a cron job (a tool that executes commands at specified time intervals.) This recovers some space on the server.

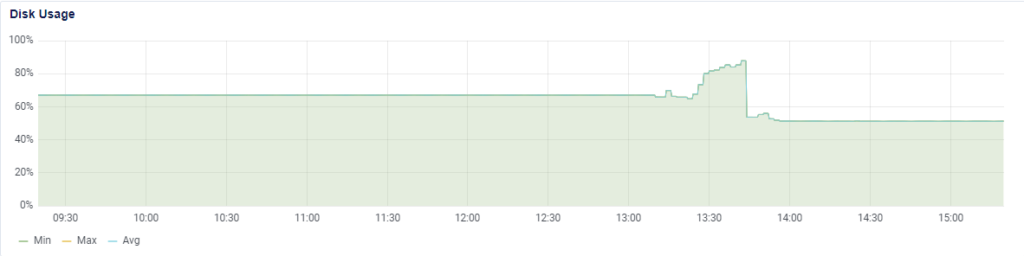

- We periodically run pg_repack (an extension for table management) on the database to reduce the size of the tables. This has only helped us regain a limited amount of storage space.

This is what the disk usage chart looked like after we ran pg_repack on the ten largest tables of our 60-GB database and got disk usage down from 69% to 51%.

Since then, we have had to bump the storage twice, first to 80 GB and a few months later to 100 GB. We are currently using 52% of that database storage space. The statuses table alone has ballooned to 19 GB. Another thing we had to do is reduce the temporary file limit in order to contain the data growth.

Apart from all that maintenance and tuning, we’ve been steadily improving hcommons.social by applying the regular Hometown updates. Our latest update was in late September and we’re super excited for the next one, which will introduce Mastodon 4.2 features, including a revamped search experience that will allow searching of posts.

All of this work was not easy, but the Mastodon community was there to help along the way. Mastodon, as an alternative to commercial social media platforms, is only viable thanks to its users and supporters. By supporting Mastodon, we have access to the Discord server, where admins and developers can share ideas and help each other. We are thankful to them and we are committed to contributing to the community as we move forward.

What’s next?

Last year as part of our #GivingTuesday campaign, we asked for funds to support site hosting, site maintenance, and establishing a moderator community for hcommons.social. Over the course of the year, as you can see, a lot of technical work has gone towards supporting our server. And so far, moderation has not needed the same amount of attention, as there has not been a large influx of reports as hcommons.social has continued to grow. Our current moderation process relies on internal review within our small team, and although we regularly receive and respond to reports, to date, we have not sought additional support on this front. To be frank, more work would be required to establish and support a moderation team than what it takes to handle things as we do now, and as a small team with big dreams we have to be judicious in where we deploy our resources. However, as our team continues to monitor reports and assess the number of reports we receive on a regular basis, we will pursue additional moderation options as we see fit. We count on your trust to make these decisions and if you see signs that our current system isn’t meeting your expectations, we very much hope you’ll let us know. Our DMs are always open.

What are your thoughts on how we’re handling moderation? If you think we should bring in more external voices, let us know!